In 2011, Sebastian Thurn and David Evans had the bright idea of recording their Stanford University lectures and posting them on the internet. The initiative was incredibly successful and hundreds of thousands of students flocked over the broadband highways to learn about artificial intelligence from two of the greatest minds in the field. In fact, their original initiative was so successful that Thurn later left his job to fund Udacity, today one of the most innovative and disruptive forces in university education. By 2012, it seemed that the whole world was talking about Massive Open Online Courses (“MOOCs”) and that MOOCs were on the path to transforming how teaching was done forever by providing the highest quality education to everyone, everywhere, for free.

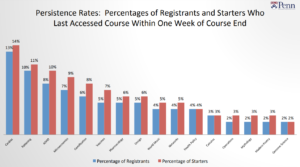

This story has a deeply personal element for me. Then an unemployed (or at times underemployed) philosophy grad, I had to make a decision about whether to go back to school to pursue yet another graduate degree, this time in computer science. I sometimes wonder what my life would have been like if I had decided to take a year off and gorge myself on an intellectual mash of Stanford videos on machine learning. I usually conclude that it would have been for the worse. I am very thankful that I ended up going back to school because I probably learned a lot more than I would have otherwise. In late 2013 and early 2014, a number of quantitative studies were published that were like a wet blanket over silicon valley’s burning fire for MOOCs. Researchers at Penn, for instance, found that as few as 5% of MOOC registrants actually finish their courses, while only a fraction of those attain high grades. What’s worse is that MOOC users were found to disproportionately come from educated, male and wealthy backgrounds, largely in the USA. So much, then, for the fad that was the MOOC revolution. Or so the story goes.

Why do MOOCs suck so much at teaching the people that they are trying to help? One of the many reasons is that they are not well-designed. Robert Ubell from NYU has been doing e-learning a long time and thinks that MOOCs suck because they were not designed to keep users engaged, like a good teacher would. Ubell points to active learning, a theory that getting students deeply involved in the learning process will produce better outcomes. For example, active learning holds that asking students questions during a lecture would produce better results because students are more deeply engaged in the process. By involving students, we can better keep their attention, which is one of the fundamental brain mechanisms governing learning. MOOCs suck at knowing when you are paying attention. Good teachers know this by the glazed look in their students eyes as their attention drifts into the mental netherworld between the classroom and PewDiePie’s latest embarrassment.

If we had a good way to measure attention, we would have a way of improving MOOCs. The problem is that scientists do not yet have reliable ways of measuring attention through a computer. Sure we can look at clicks or scrolls, but do clicks really tell you much when you are rewarded by faking it? Alternatively, we could ask you whether you are paying attention, but this will disrupt the course experience. This is why I am looking at brain data. If we watch people’s brains, we can reliably understand when they stop paying attention, and maybe build MOOCs that teach better. It’s a bold idea, but if it works, we could develop technologies that achieve this original vision: quality education for everyone, everywhere, for free.